Saturating media today probably more than any monster, zombies have so persistently infected pop-culture not only through fear of their countless variants but what the creature represents: The personification of death & the unknown. Outside generations of varying socio-political commentaries, the undead have from one perspective always symbolized death’s creeping inevitability, possibly the most primal fear we can connect with regardless of cultural differences. Whether it’s the suspense of not knowing if/when/how they’ll catch you, how long you can stay a step ahead, debating what the point of it all is, or whether to end it on your own terms, the Hollywood zombie’s unique approach thoroughly embodies this.

Moreover, what better, more natural, relatable vehicle for this concept than a plague? Be it viral, fungal, bacterial, radiation, supernatural, or aliens, the base-concept of “If it gets you, you become one of them” works. The simple but cruelly brilliant psychological warfare of infected loved ones as a deterrent against necessary measures to eliminate the threat reflects actual history of families forced to quarantine or kill & bury their own. The Black Death’s reduction of the world population by an estimated 25 million from 1347-51 is one infamous example not lost on privileged 1st world civilizations.

Unlike the link between death & sexuality common in vampires, however, zombies don’t require the allure of special powers to stand out. Their numbers alone speak volumes, as most fiction in which the dead gradually outnumber the living inherently builds a sense of isolation reminiscent of 1954’s I Am Legend (the novel that would strongly inspire the late horror pioneer George A. Romero). The existential dread of adapting to life as a progressively endangered minority slowly deteriorates sanity and agency almost to a claustrophobic degree, even out in the open as the world (metaphorically) shrinks around you.

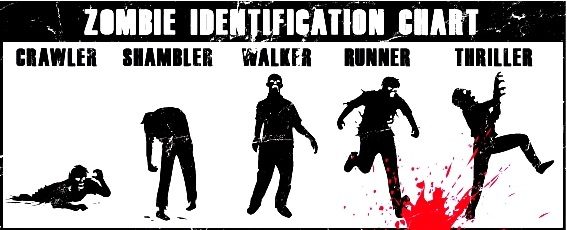

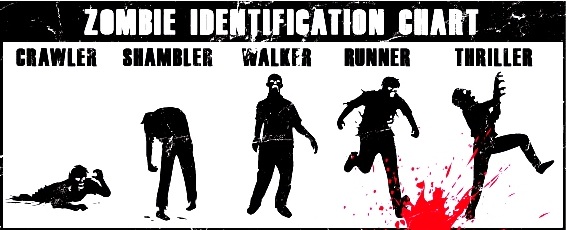

To quote The Zombie Survival Guide and World War Z author Max Brooks, survival becomes an equivalent of “the tortoise and the hare, adding that the hare stands a good chance of being eaten alive,” another psychological blow to morale. Beyond death, however, is what comes next. Is there an afterlife? If I reanimate, will some part of me stay self-aware, trapped inside myself, aimlessly wandering, consuming until I rot away? This unknown factor builds the horror further. Yes, several believe sprinting zombies directly undermine these values. As Romero put it:

“Partially, it’s a matter of taste. I remember Christopher Lee’s mummy movies where there was this big lumbering thing walking towards you and you could blow it full of holes, but it would keep coming. In the original Halloween, Michael Myers just calmly walked across the lawn or room. To me, that’s scarier: This inexorable thing coming at you and you can’t figure out how to stop it. Aside from that, I do have rules in my head of what’s logical and what’s not.”

Where was that line drawn? In his words, “I don’t think zombies can run. Their ankles would snap!” And yet, have physically & mentally quicker undead not been influential in film as well since long before the 2000’s re-popularized them (Ex- Night of the Living Dead co-screenwriter John A. Russo’s Return of the Living Dead series)? Controversy among Romero die-hards aside, do many values above not portray themselves throughout the Dawn of the Dead remake in their own right? The key difference in tone is derived from the zombies themselves, sacrificing subtlety for an arguably superior predator.

Taking everything Romero practically wrote the book on and in multiple respects turning it on its head, the most recognizable incarnations of these runners retain a classic zombie’s most terrifying advantage over humans, virtually unlimited stamina. By adding improved coordination + some lingering semblance of intelligence, this particular trait is exploited to another dimension of formidability that would make triathletes jealous as they race, jump, and climb after their target for miles. While they can at first glance look similar, these were a different beast altogether that fundamentally changed the apocalypse into a whole new ballgame.

Their heightened speed, agility, and in some cases insect-like swarming is often matched by the quicker rate at which the source of zombification affects its host. Whereas a classic victim could have the process play out over hours, a runner can be created in seconds. Even with Romero’s beloved shamblers’ continued success in properties like The Walking Dead, they have admittedly lost a step in attention while runners have gained a progressively substantial lead on the big screen alone (28 Days/Weeks franchise, Zombieland, 2013’s World War Z adaptation, etc.).

Looking back before this unlikely reinvention impacted cinemas though, over six years before Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later swept the UK, another more interactive medium was sending it in our faces: Video games. On March 22, 1996, we got our first major nightmare fuel for the archetype with far more pep in its step- through Capcom’s Resident Evil (Biohazard, in Japan) in the form of… zombie-dogs! Responsible for one of the most universally effective jump-scares in visual storytelling, players’ first encounter with these undead Dobermans immediately made clear that your journey to Hell and back in this haunting mansion would be filled with twists & surprises. You couldn’t casually stroll around them as was possible with the walking corpses that greet you, nor did they go down as easily.

The idea would later expand (This time, a few months before 28 Days Later’s release) in 2002’s praised Resident Evil remake, which debuted a faster evolution of classic zombies we’d come to know & love to hate as the Crimson Head. Since then, you can’t find nearly as many genre entries that don’t involve some offspring of the runner template, from series like Call of Duty’s zombie modes to Left 4 Dead, Dead Space, Dead Island, and its successor Dying Light to name a few.

So, how & why did what are on paper essentially zombies on steroids take off (pun intended)? Does “stronger, faster, better” apply here? To understand one explanation for this acclaim, let’s consider how fans have changed. The hordes of old aren’t as threatening to an ever-growing minority of viewers now, chiefly due to how society’s means to combat & seek information on disaster scenarios have grown. To justifiably play the “current year” card, it’s not 1968, ’78, or ’85 anymore.

Before the internet, which offers infinitely more avenues for independent research to educate ourselves and react accordingly, the idea of a global invasion involving creatures that defied all laws of science was perceived as scarier. Our smaller range of outlets back then left most more dependent on news presented to them rather than explored (TV’s few channels, newspaper, radio). When these felt unreliable in times of crisis due to conflicting info, paranoia could lead to panic.

Perhaps at no points in history were this media distrust fostering more division among Americans than during the Cold War and Vietnam, the latter of which ‘68’s Night of the Living Dead was a commentary on. Once the digital age took over and we gained tools to connect globally at the push of a button, the ritual of gathering around the TV, turning up a station, or waiting for papers to absorb current events diverged more into the individuality of mobile devices and online chats.

Despite The Shawshank Redemption’s early 20th century setting, I think Brooks Hatlen said it best: “The world went and got itself in a big damn hurry.” With such technology, which has helped sell the illusions of fiction on another level from what was doable 30-40 years ago, we have an entire world at our finger-tips capable of gathering vast data in seconds. Sound familiar? In a sense, this cultural acceleration mirrors the boost represented in fast zombies. Just as modern times have sped up availability & versatility of information/communication, the zombie threat in turn was given a new shot of adrenaline to compensate.

Imagine how well or poorly we could organize in time against a shambler outbreak that can take days-months vs. an onslaught by more aggressive hordes charging like hungry wolves at our doors & windows before we can process what’s happening (Ex- 28 Weeks Later’s opening)? Compare it to the distinction between a building flood and a rushing tsunami. Some value danger factor more for its greater immediate advance + epidemics trading ambiguity for something relatively closer to plausible such as the now common trope of mutated Rabies, Ebola, or Mad Cow playing on our fears of wild and diseased animals.

Not every zombie lover resonates with the more symbolic suspense of slower, limping ghouls but BOTH fears are valid. Granted, I understand those who dislike runners. After all, their higher energy, at times obnoxiously loud sounds, and overall spectacle is a stark contrast. If a runner apocalypse comes, my already slim survival odds virtually vanish! Comment below, what do you think of slow zombies’ influence vs. fast zombies? Do you find either inherently less scary?

#Runners or #Shamblers